North Atlantic haddock use magnetic compass to guide them

A new study has found that the larvae of haddock, a commercially important type of cod, have a magnetic compass to find their way at sea. Haddock larvae orient toward the northwest using Earth's magnetic field.

Scientists at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and the Institute of Marine Research in Norway used a unique combination of experiments to track larvae movements, using a magnetoreception test facility, or MagLab, and a Norwegian fjord, a natural environment of Atlantic haddock larvae.

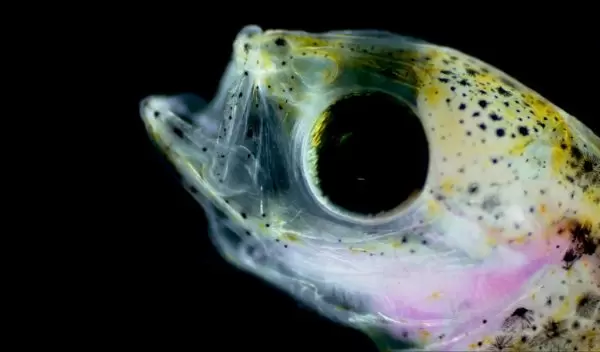

Researchers observed the larvae in a transparent behavioral chamber, developed by the University of Miami's Claire Paris, under the environmental conditions they would encounter at sea. The larvae were also tested in the MagLab, where the magnetic field to which they were exposed was rotated such that the North-South and East-West were shifted by 90 degrees for each of the larvae.

The scientists found that the larvae oriented to the magnetic northwest in the chamber, and, although deprived of all other environmental cues, oriented toward the same magnetic direction in the MagLab.

"These microscopic haddock larvae were born in a hatchery and had never experienced life at sea, which suggests that magnetic orientation is in their DNA," said Paris, senior author of the study.

The discovery is an important step in better understanding the early-life stages of this commercially valuable fish, the authors said. The research was published in the journal iScience.

"This internal compass can help orient animals who live in a complex, dynamic three-dimensional habitat,” said Mike Sieracki, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research. “If adults retain this ability, it would help them with migration between feeding and spawning areas.”