Reducing nutrient pollution helps corals resist bleaching

Reducing nutrient pollution can help prevent coral reefs from bleaching during moderate heatwaves, according to a National Science Foundation-funded study by researchers at UC Santa Barbara. The results, which appear in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offer new strategies for managing these highly threatened and important ecosystems.

Reef-building corals host beneficial algae in their tissues. In exchange for protection and nitrogen, the algae provide the coral with food. All is well until the water gets too warm.

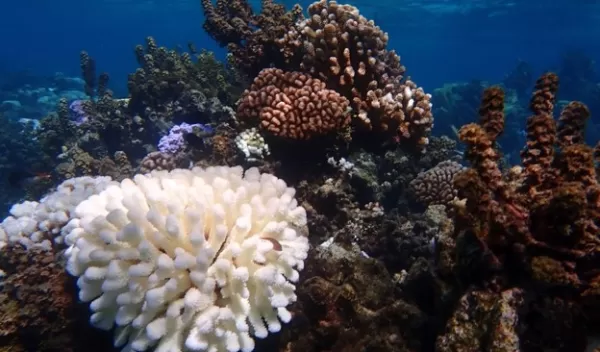

At higher temperatures, the algae's photosynthesis goes into overdrive, and the chemical balance between the coral and the algae breaks down. At a certain point, the coral and its tenant part ways in a process known as bleaching. Coral can survive for a time without algae, so recovery is possible if conditions return to normal quickly. But in the absence of its partner, the coral will starve and eventually die. The worse the bleaching is, the more likely that is to happen.

Experiments in the lab, as well as in a few small field studies, suggested that nitrogen pollution, such as from fertilizer and sewage runoff, could exacerbate bleaching. Excess nitrogen in the water can short-circuit the beneficial partnership between corals and algae.

However, it was not known whether nutrient effects on bleaching occurred in many corals over large areas. So marine biologists decided to investigate the effects of nitrogen on coral bleaching -- on the scale of an entire island -- as part of the NSF Moorea Coral Reef Long-Term Ecological Research site in French Polynesia.

The scientists looked at the two most common types of branching coral in Moorea. They found that nutrient-exposed corals were more sensitive to temperature.

"This research demonstrates that managing local stressors like nutrient pollution makes corals more resistant to temperature stress," says Daniel Thornhill, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences. "The knowledge will be helpful for resource managers and will buy time to address the global threat reefs face due to warming, acidifying oceans."