Reflecting on the Many Uses of Glass

Research in glass has changed nearly everything, from architecture to communication, yet glass research has become a more fractured endeavor. Privately funded labs have closed, and universities in the United States and England that were once glass research bulwarks have changed their research focus. Meanwhile, scientists in other countries, particularly in Japan, are increasingly interested in the potential of glass research.

Himanshu Jain, professor of materials science and engineering at Lehigh University, is both a materials scientist and an educator. He is a recognized leader in developing highly sophisticated forms of glass for biomedical sensors, communications, microelectronics and a range of other uses, and a fervent believer in providing underrepresented groups access to cutting-edge research.

Jain is also the director of NSF's International Materials Institute for New Functionality in Glass (IMI-NFG) at Lehigh, a center that brings researchers from around the world together with students to develop the latest glass technology.

"Innovation and curiosity aren't bound by cultural differences or geographic boundaries," says Jain. "Great ideas come from all corners of the world, so as researchers, we must actively pursue opening new doors, wherever possible."

Short course on glass at Tuskegee

NSF created six IMIs to encourage learning across national borders, each center focusing on a different specialty. Jain co-directs IMI-NFG with Carlo Pantano of Pennsylvania State University.

"We have two goals, one is research and the other is education," Jain says. "We aim to educate and excite people from all educational levels and cultural or national backgrounds about the possibilities inherent in scientific research in general, and glass science in particular."

To help broaden access to the field of glass science research, Jain and Pantano proposed, developed and delivered a short course on glass science and engineering to students at Tuskegee University, a historically black institution of higher learning in Alabama.

Even though minority participation in science and engineering has gradually increased, a recent NSF study shows merely 4 percent of academic positions in these fields are held by African Americans.

"Our hypothesis was that the students from Tuskegee would engage more completely in an environment in which they felt most comfortable, rather than being transplanted to an unfamiliar surrounding for a limited time," says Jain.

Jain and Pantano initially planned to incorporate their lectures into an existing Tuskegee physics course. However, they were pleasantly surprised to learn that the number of students who wished to take the course far exceeded the course's normal capacity.

Great story of glass

The IMI-NFG short course was designed to introduce students to the fundamentals: structure, properties, processing and manufacturing of glass. Seventeen one-hour lectures were presented by Jain and Pantano, including demonstrations and videos to generate excitement among the students.

Jain and his colleagues had a great story to tell. Glass, it seems at first glance, is almost endlessly versatile. We use glass to repair our eyesight, to adorn skyscrapers and to create artistic treasures. We employ it to reflect, refract and transmit light, and to exchange unthinkable quantities of information in slices of seconds. But all this is just the surface, says Jain. If we can learn to tailor its chemical and mechanical properties, glass may be used to mimic and even restore the miracles of nature, he predicts.

Through work with collaborators at Lehigh, Princeton University, the University of Delaware and across three continents, Jain and his colleagues are engineering a biocompatible glass into a scaffold that promises to stimulate the healing of broken bones.

Biocompatible glass for healing bones

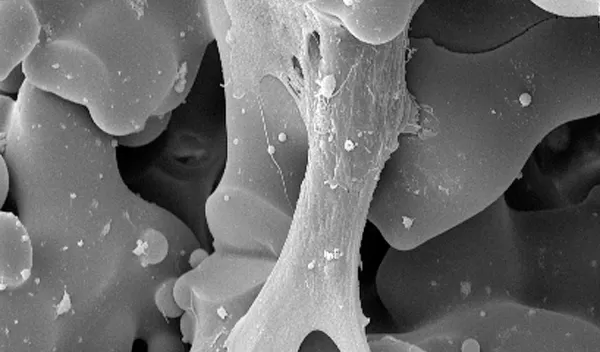

Like the spongy interior of human bone, the new material will have interconnected pores to aid the growth of bone cells and the flow of blood. The research team is attempting to match the biochemical and mechanical properties of bone with glass scaffolding that is porous at both the nano- and macro-scales.

Nanopores, measuring just a few nanometers (billionths of a meter) in diameter, allow cells to adhere and bone material to crystallize. Macropores, with diameters of about one hundred microns (millionths of a meter) across, allow bone cells to grow inside the scaffold and to vascularize, or form new blood vessels and tissue.

"We believe this material will stimulate bone regeneration because cells will proliferate inside the scaffolding material and form tissue, thus facilitating the delivery of nutrients for bone regeneration," says Lehigh professor Matthias Falk, a cell biologist and IMI-NFG collaborator.

"When you attach the glass to the damaged bone, a layer forms on the surface of the glass that has the same chemical composition as the natural bone," says IMI-NFG collaborator Mohamed Ammar of the University of Alexandria (Egypt) tissue engineering lab. "The bone cells come to this layer and attach to it, in effect, forming a bone matrix around the glass."

Other applications for the material include drug delivery and the separation of viruses from blood, work that is ongoing in the laboratory of Lehigh collaborator Xuanhong Cheng.

Attracting more underrepresented students

The students in the short course were hooked. The activity was a highly successful experiment in generating the interest of African American students in glass science and engineering, and Jain now wants to see the effort applied to other branches of science and engineering in the future.

Jain, Pantano and Tuskegee faculty are moving ahead with plans to turn the lectures into repeatable Tuskegee course material, to be taught as a combination of intensive live lectures and distance learning. In addition, many Tuskegee students expressed interest in the NSF-sponsored Research Experiences for Undergraduates programs at Lehigh and Penn State.

"Our partnership with Tuskegee University will be mutually beneficial for developing collaborations in research as well as education," Jain said. "It has opened doors for attracting bright African American students to Penn State and Lehigh for pursuing careers in science and engineering. The resources represented by IMI-NFG will further ensure that these students have access to the global pursuit of science and technology."

-- Chris Larkin, Lehigh University chris.larkin@lehigh.edu

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.