Researchers begin to decipher the sea urchin microbiome

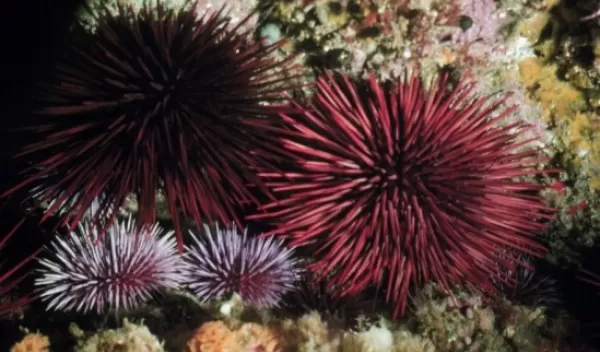

Sea urchins receive a lot of attention in California. Red urchins support a thriving fishery, while their purple cousins are often blamed for mowing down kelp forests and creating urchin barrens. Yet for all the notice we pay them, we know surprisingly little about the microbiomes that support these spiny species.

U.S. National Science Foundation-funded researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara led by geneticist Paige Miller sought to uncover the diversity in the guts of these important kelp forest inhabitants. The results reveal significant differences between the microbiota of the two species -- red urchins and purple urchins -- as well as between individuals in different habitats. The work was done at the NSF-funded Santa Barbara Coastal Long-Term Ecological Research site.

The study, which appears in Limnology and Oceanography Letters, represents the first step in understanding the function of urchins' microbial communities, including the possibility that urchins may be able to "farm" microbes in their guts to create their own food sources.

Both red and purple sea urchins consume algae but are fairly opportunistic omnivores that will eat decaying plant and animal matter, microbial mats and even other urchins. The microbiome in their guts might help urchins handle such a varied diet, but this possibility hasn't been examined until now.

"It's important to understand what animals eat and why," Miller said, "and we think the microbiome could play an important role in why species thrive despite all the variation in food availability that's out there in the ocean." However, scientists are only beginning to investigate the microbiota of ocean animals, let alone the function these microorganisms serve in their hosts.

To begin their investigation, Miller and her team collected red and purple urchins from three habitats in the Santa Barbara Channel: some from lush kelp forests, others from urchin barrens, and a few from one of the channel's many hydrocarbon seeps, where they scratch a living from mats of microbes that thrive on petroleum compounds.

The team found significant differences in the bacterial communities living in the two urchin species. However, they saw just as much variation between the microbiomes of individuals from the same species living in different habitats.

"Our study is the first to examine the microbiome in these extremely common, and ecologically important, species," said co-author Bob Miller, a researcher at UC Santa Barbara's Marine Science Institute. "We're just scratching the surface, but our study shows how complex these communities are."