Scientists discover immense biodiversity in high-temperature, deep-sea microorganism communities

A new study by researchers at Portland State University and the University of Wisconsin finds that a rich diversity of microorganisms lives in interdependent communities in high -temperature geothermal environments in the deep sea.

The study, published in the journal Microbiome, was led by Anna-Louise Reysenbach at PSU.

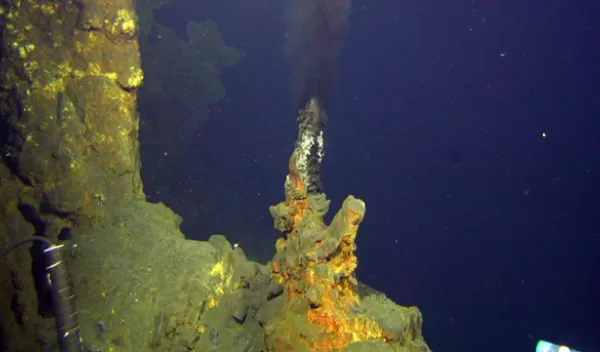

When the 350-400 degree C fluid exiting the Earth's crust through deep-sea hydrothermal vents mixes with seawater, it creates large, porous rocks often referred to as chimneys or hydrothermal deposits. These chimneys are colonized by microbes that thrive in high-temperature environments.

Reysenbach has collected chimneys from deep-sea hydrothermal vents in the world's oceans. Her lab uses genetic fingerprinting and cultivation techniques to study the microbial diversity of the communities associated with these rocks.

In the U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study, Reysenbach and the team were able to take advantage of advances in molecular biology techniques to sequence the entire genomes of the microbes in these communities to learn more about their diversity and interconnected ecosystems.

"This research demonstrates the incredible diversity of microbial communities in the extreme environments of deep-sea hydrothermal vents throughout the ocean basins," says Gail Christeson, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences.

The team constructed genomes of 3,635 bacteria and archaea from 40 rock communities. The diversity was staggering, according to the scientists, and greatly expands what is known about how many different types of bacteria and archaea exist.

The researchers discovered at least 500 new genera (the level of taxonomic organization above species) and have evidence for two new phyla (five levels up from species). The team also found evidence of microbial diversity hotspots. Samples from the deep-sea Brothers Volcano near New Zealand, for example, were enriched with microorganisms, many endemic to that volcano.

"That biodiversity was just so huge," says Reysenbach. "At one volcano there was so much new diversity that we hadn't seen elsewhere." The finding suggests that the increased complexity of the subsurface rocks of a volcano makes them more likely to house diverse microbial species compared to deep-sea hydrothermal vents.