Scientists discover new and unusual species of diatoms in waters off Hawaii

Scientists have discovered two new and unusual species of diatoms in the waters off Hawaii, they report in Nature Communications. The U.S. National Science Foundation-funded researchers at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, University of California Santa Cruz, and California State University San Marcos found that the organisms fix nitrogen, a critical process that supports productivity in the nutrient-poor open ocean they inhabit.

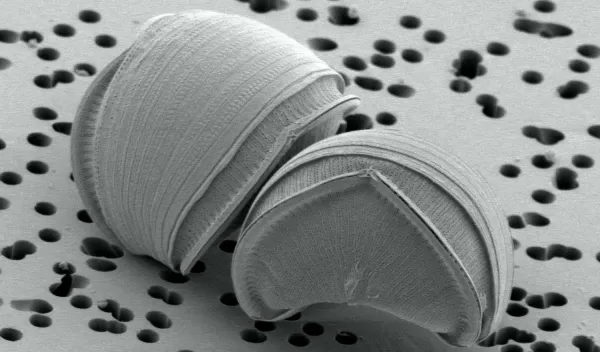

Diatoms, with their intricately patterned cell walls made of glassy silica, are some of the most well-known phytoplankton. They fare best in nutrient-rich conditions.

In the nutrient-poor open ocean waters around Hawaii, diatoms struggle to acquire enough nitrogen to grow. To solve this problem, some diatoms have established symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. These cyanobacteria can take dissolved nitrogen gas -- which is plentiful in seawater but not accessible to the diatoms -- and convert it to ammonia, a form of nitrogen the diatoms can easily use, but which is otherwise sparse in the open sea.

By harboring the cyanobacteria inside their glass houses, diatoms have their own personal nitrogen generators. They become a self-fertilizing system.

"Oceanographers have known about these diatom-cyanobacteria symbioses in waters around Hawaii for many years," said Christopher Schvarcz, lead author of the study, "but the species we discovered are something quite different."

The new diatom species are smaller and belong to a different lineage with an elongated, or "pennate" shape with bilateral symmetry. Their symbionts are also smaller and unicellular, and they do not glow under fluorescent light because they do not contain chlorophyll, making them nearly invisible inside the diatom.

That likely explains why they went undetected for so long. The scientists discovered the new species by adding samples of seawater to nitrogen-poor growth medium in the lab, then carefully examining the cultures under a microscope over a period of weeks to months to see what phytoplankton would grow.