Warm oceans helped first human migration from Asia to North America

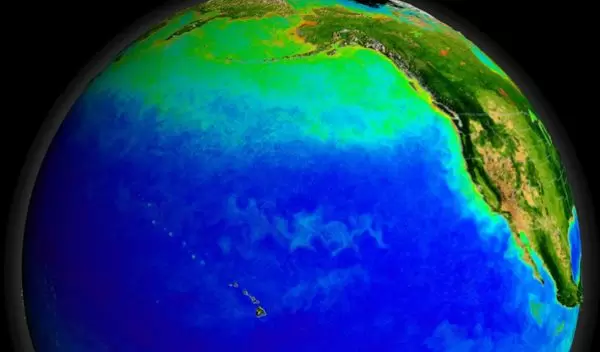

New research reveals significant changes in the circulation of the North Pacific Ocean and their impact on the initial migration of humans from Asia to North America.

The U.S. National Science Foundation-funded study published in Science Advances provides a new picture of the circulation and climate of the North Pacific at the end of the last ice age, with implications for early human migration.

Scientists used sediment cores from the deep sea to reconstruct the circulation and climate of the North Pacific during the peak of the last ice age. The results reveal a dramatically different circulation in the ice age Pacific, with vigorous ocean currents creating a relatively warm region around the modern Bering Sea.

The warming from these ocean currents created conditions favorable to early human habitation, helping address a long-standing mystery about the earliest inhabitants of North America.

"According to genetic studies, the first people to populate the Americas lived in an isolated population for several thousand years during the peak of the last ice age, before spreading out into the American continents," said co-author Ben Fitzhugh of the University of Washington.

That has been termed the "Beringian Standstill" hypothesis. A significant question is where the population lived after separation from Asian relatives and before deglaciation allowed them to reach and spread throughout North and South America.

The new research suggests that these early Americans may have dwelled in a relatively warm refugium in southern Beringia, on now-submerged land beneath the Bering Sea. Due to the extremely cold climate that dominated other parts of this region during the ice age, it has been unclear, until now, how habitable conditions could have been maintained.