Were the ancient Maya an agricultural cautionary tale? Maybe not, new study suggests

For years, climate scientists and ecologists have held up the agricultural practices of the ancient Maya as prime examples of what not to do.

"There's a narrative that depicts the Maya as people who engaged in unchecked agricultural development," said Andrew Scherer, an anthropologist at Brown University. "The narrative goes: The population grew too large, the agriculture scaled up, and then everything fell apart."

But a U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study, co-authored by Scherer and others, suggests that narrative doesn't tell the full story.

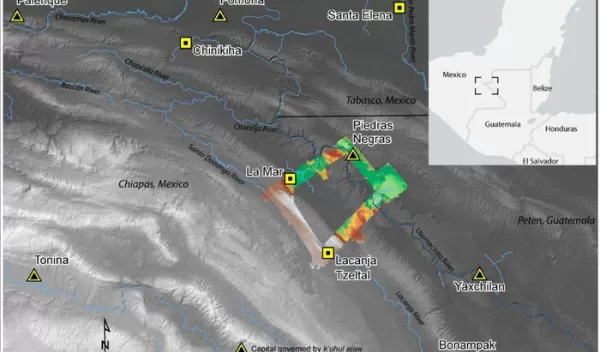

Using drones and lidar, a remote sensing technology, a team led by Scherer and Charles Golden of Brandeis University surveyed an area in the Western Maya Lowlands situated at today's border between Mexico and Guatemala.

Scherer's lidar survey -- and later boots-on-the-ground surveying -- revealed extensive systems of sophisticated irrigation and terracing in and outside the region's towns, but no huge population booms to match. The findings demonstrate that between A.D. 350 and 900, some Maya kingdoms were living comfortably, with sustainable agricultural systems and no demonstrated food insecurity.

"It's exciting to talk about the really large populations the Maya maintained in some places; to survive for so long with such density was a testament to their technological accomplishments," Scherer said. "But it's important to understand that that narrative doesn't translate across the whole of the Maya region. People weren't always living cheek to jowl. Some areas that had potential for agricultural development were never even occupied."

The findings were published in the journal Remote Sensing.

Scherer said he hopes the study provides a more nuanced view of the ancient Maya -- and perhaps even offers inspiration for members of the modern-day agricultural sector who are looking for sustainable ways to grow food for an ever-growing global population.