Whole-genome analysis offers clarity on remains of 36 enslaved Africans in 18th-century Charleston

The city of Charleston, South Carolina, has been on a quest to better understand the remains of 36 people described collectively as "the Ancestors" since their chance discovery a decade ago in the city's center.

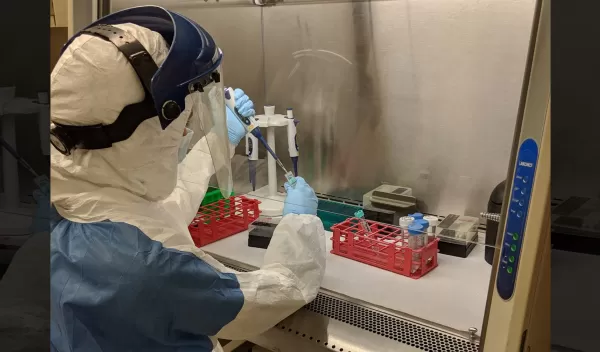

In 2020, a team from the University of Pennsylvania and the nonprofit Gullah Society, whose mission was to reclaim African and African American burial sites around Charleston, made progress by sequencing the Ancestors' mitochondrial DNA.

The research showed that most of the individuals had originated in Charleston or sub-Saharan Africa and, given the burial ground's location, had likely been enslaved. At the time, that work was the largest DNA study of its kind. It was also unique in its aim to involve the Charleston community from the start, guided by the questions and concerns of the people directly affected by what the researchers might find.

New research has built on that previous work. The U.S. National Science Foundation provided support through a postdoctoral research fellowship to Raquel Fleskes, first author of a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Through whole-genome sequencing, the researchers confirmed that most of the people had West African or West Central African genetic ancestry and were genetically male.

The team also verified that only one mother-child pair was related. The researchers say that, taken as a whole, these findings significantly increase what's known about African diversity in colonial America.

The project grew out of feedback from the community, prompting the Gullah Society to advocate for a scientific inquiry centered around answers sought by the local African American community. "Our aim has always been to do science that doesn't objectify these remains but rather tries to restore personhood to them," says Fleskes.

Fleskes, Penn anthropologist Theodore Schurr, and other team members started by analyzing mitochondrial DNA, the genetic material inherited from the female line alone and a frequent starting point for research of this kind. That revealed broad information about the individuals' background and demography but couldn't go as deep as whole-genome sequencing would. Archival maps and subsequent bone analysis led the researchers to conclude that the remains belonged to enslaved people.

As a next step, the team conducted a more extensive analysis. In conjunction with material from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, the data provided greater clarity on the Ancestors' genetic history. The researchers found that nine Ancestors had DNA that aligned closely with populations from regions that today make up the country of Gabon in West Central Africa, and nine had DNA that lined up with reference populations now in the countries of Ghana, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. In addition, 21 of the 27 individuals were chromosomal males.

"We've also been able to confirm that at least one of those individuals has a genetic signature that shows mixing with a person of Native descent," says Schurr. "That's interesting because the first people enslaved in Charleston were Native Americans. Shortly thereafter, African people were brought to colonial America as forced labor."