When was NSF established?

The U.S. National Science Foundation was established as a federal agency in 1950 when President Harry S. Truman signed Public Law 81-507, the "National Science Foundation Act of 1950."

Since then, NSF has supported basic research — research driven by curiosity and discovery — at colleges, universities and other organizations across the country for over seven decades.

While NSF has grown and evolved since 1950, its mission has remained the same: "To promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare; and to secure the national defense; and for other purposes."

Why was NSF formed?

The seeds for NSF were planted years before it was established, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized the crucial role that the scientific enterprise was playing in the Allied success in World War II.

Before World War II, the federal government played a minor role in supporting research at U.S. colleges and universities. Instead, research institutions relied on philanthropic endowments or funding from private companies, often with vested interests. "Curiosity-driven" science, a cornerstone of discovery and innovation, was stymied in the process.

In November 1944, thinking ahead to the end of the war, Roosevelt wrote to director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development Vannevar Bush, asking how the successful application of scientific knowledge to wartime problems could be carried over into peacetime — and requesting recommendations on a national policy for science.

In 1945, Bush presented his report, "Science: The Endless Frontier," to President Harry S. Truman. The report envisioned a new agency whose mission would promote the progress of science by supporting basic research at colleges and universities.

In 1950, following a series of bill revisions, Congress passed and President Truman signed Public Law 81-507, establishing the National Science Foundation and the National Science Board. NSF's place in history was cemented.

How has NSF changed?

NSF has grown and adapted to meet societal needs in the decades since it was formed. To advance the performance of research, new directorates and programs have been created and new awards developed.

Some notable changes across the agency over the last 70 years include an expanded portfolio, charged with diversifying STEM and broadening participation. In 1952, for example, NSF funded fellowships for graduate students. Today, the Directorate for STEM Education has grown to support students and teachers at all grade levels, strengthening STEM learning through initiatives that promote access and inclusivity.

New directorates have also been established at NSF: Engineering in 1981; Computer and Information Science and Engineering in 1985/86; and Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences in 1991. And in 2022, NSF's Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships — its first new directorate in 30 years — was formed to bridge curiosity-driven and use-inspired research and grow industry, create new jobs, and cultivate an equitable STEM workforce across the nation.

In the years to come, NSF will continue to grow and evolve to meet the challenges of the day. Yet, NSF's mission — "to promote the progress of science" — remains steadfast.

NSF's history and impacts: a brief timeline

1944 - November 17

President Franklin D. Roosevelt writes Vannevar Bush, director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, asking how the successful application of scientific knowledge to wartime problems could be carried over into peacetime.

1945 - July 5

Vannevar Bush presents a detailed report to President Harry S. Truman. Among the recommendations in "Science: The Endless Frontier" is the establishment of a foundation to oversee federal funding for basic scientific research and the training for workers in science. Read the report.

1945 - July 19

Senator Warren Magnuson introduces a bill to implement Bush's plan, the first of several offered. In later bills, the proposed name is the "National Science Foundation," a title first suggested by Senator Harley M. Kilgore in 1945.

1950 - May 10

Congress passes and President Harry S. Truman signs Public Law 81-507, creating NSF. The act provides for a National Science Board of 24 part-time members and a director as chief executive officer. The board's first meeting is held Dec. 12.

1951 - March

Alan T. Waterman, chief scientist at the Office of Naval Research, is nominated by President Harry S. Truman to become the first director of NSF. The agency is provided with an initial appropriation of $225,000.

1952 - February 1

The National Science Board approves the first 28 research grants to be awarded by NSF. The first grant, for $10,300, goes to the Institute for Cancer Research. A total of 97 research grants are awarded in the first year. Among the recipients is Max Delbruck (Nobel Prize in in physiology or medicine, 1969).

1952

NSF launches the Graduate Research Fellowship Program to support outstanding graduate students in NSF-supported STEM disciplines. It will become NSF's longest continuously operating program.

1955

The first planning grants are given for the establishment of national radio and optical astronomical observatories.

1956

NSF awards its first grants to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and to what would become the Kitt Peak National Observatory. Construction begins on NRAO in Green Bank, West Virginia. The observatory is completed in 1962.

1957 - January 22

The South Pole station is officially dedicated. The U.S. has six scientific stations established in Antarctica, all funded by NSF. The 1957–58 International Geophysical Year was a global effort to collect data in many fields.

1957 - October 4

The Soviet Union launches Sputnik I, the first satellite, into orbit. This triggers a national self-appraisal of scientific research and education, and the U.S. Congress responds by more than doubling the NSF appropriation to $134 million, beginning July 1, 1958.

1959

NSF develops the National Center for Atmospheric Research. It will begin operating in 1960 in Boulder, Colorado, as an NSF program managed by the nonprofit University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

1959 - August 25

President Dwight D. Eisenhower signs Public Law 86-209, establishing the National Medal of Science, awarded to individuals for their outstanding contributions to areas of science.

1960s

During the 1960s, NSF funds, in part, research that leads to the creation of data compression algorithms. The technology is first used for satellite transmissions but today is used in everyday items like TVs and computer hard drives, to name a few.

1963 - July 1

Leland J. Haworth becomes the second director of NSF (1963–1969).

1965

In the 1960s, an English professor and linguist at Gallaudet College, William Stokoe, begins to look at American Sign Language and discovers that it is full of regularities and structure, like a spoken language. With an NSF grant, he publishes the dictionary of ASL.

1968 - July 18

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs Public Law 90-407, amending the NSF authorization act, making explicit support for the social sciences and applied research, and charging NSF with fostering development of computer and other scientific technologies.

1969 - July 14

William David McElroy becomes the third director of NSF (1969–1972).

1969 - October 1

The Pentagon transfers ownership of Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico to NSF. This is one of the largest centers for research in radio astronomy, planetary radar and terrestrial aeronomy. The huge "dish" is 1,000 feet in diameter, 167 feet deep and covers an area of about 20 acres.

1970s

Research by NSF-funded scientists on solid modeling leads to widespread use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing, or CAD/CAM, which revolutionizes many manufacturing processes.

1970s

NSF helps fund barcode research, which, in turn, helps to perfect the accuracy of the scanners that read barcodes.

1970 September 1

The Office for the International Decade of Ocean Exploration is established. This is one of several large-scale projects in oceanography that NSF has led or participated in.

1971

NSF's Division of Materials Research is established in 1971 to take over the Department of Defense's materials science portfolio, following the 1969 Mansfield Amendment restricting DOD to mission-related research. NSF becomes the leading funder of materials research at U.S. universities.

1971 - February 1

Research Applied to National Needs, or RANN, is established. The sometimes-controversial effort seeks to solve contemporary domestic problems like pollution, transportation and the energy crisis through the application of academic research. It is disbanded in 1978.

1971 - September 10

NSF Director William McElroy announces the foundation's commitment to improving the quality of science education and strengthening the research capability at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs.

1972

Launch of the "Science and Engineering Indicators," a biennial report to Congress and the president, composed by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics.

1972 - February 1

H. Guyford Stever assumes the directorship of NSF (1972–1976).

1973

NSF takes over support of the deep-sea research submersible Alvin. Built for the Navy in 1964 and still working today, Alvin will discover life in the extreme environment of deep-sea vents in 1977 and complete its 5,000th dive in 2018.

1975 - August 9

The Alan T. Waterman Award is established by Congress. The award recognizes an outstanding young researcher in any of the fields supported by NSF.

1977 - May 3

Richard C. Atkinson is confirmed by the Senate to be NSF director (1977–1980).

1978 - January 19

To improve the geographic distribution of grants and help underrepresented states improve research competitiveness, the National Science Board approves the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR. May 1979 saw the first grants.

1980s

There are some five foundational patents from which additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, arose. NSF was critical to at least three of these. The first filed was for selective laser sintering in 1986. Others were sheet lamination and binder jetting.

1980s

Buckyballs are clusters of 60 carbon atoms, forming a polyhedral structure, like a soccer ball. Such carbon structures are fundamentally novel materials. In 1996, U.S. researchers Robert F. Curl Jr. and Richard E. Smalley, funded by NSF, shared two-thirds of the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

1980s

Challenged to improve research and education in engineering and to shorten the time between discovery and application, in 1985, NSF launches the Engineering Research Centers. In 1987, the Science and Technology Centers expand the concept to other disciplines.

1980s

Research funded by NSF at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and at universities is instrumental in the development of Doppler radar as a meteorological research tool, including mobile Doppler on Wheels. Doppler radar is commonly displayed in weather prediction and reporting.

1980 - September 23

John B. Slaughter is confirmed by the Senate as director of NSF (1980–1982).

1981 - March 8

In a major reorganization, NSF establishes the Directorate for Engineering, giving new emphasis to engineering research.

1982 - June 21

NSF-funded researchers announce the discovery of the oldest known hominids. The approximately 4-million-year-old specimens are of Australopithecus afarensis, whose best known member is Lucy.

1982 - November 3

Edward A. Knapp becomes director of NSF (1982–1984).

1982 - 1989

In 1982, NSF's education funding is cut, but global competition leads President Reagan to increase K-12 funding and create the NSF-administered Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching. By 1990, the Education and Human Resources directorate is established.

1984 - August 6

Erich Bloch is confirmed by the Senate as director of NSF (1984–1990).

1985 - February 25

NSF announces funds for National Advanced Scientific Computing Centers. The centers enable researchers to model everything from molecules to the structure of the early universe. NSF links the centers and its regional university network to form NSFNET, forerunner of the internet.

1985 - 1986

NSF establishes supercomputing centers at Cornell, the University of Illinois, Carnegie Mellon University/University of Pittsburgh, University of California San Diego and Princeton Univeresity. Since then, NSF has supported many other supercomputers like Stampede in Texas and Blue Waters in Illinois.

1986

In 1965, an NSF-funded investigator discovered a bacterium in the extreme temperatures of the hot springs in Yellowstone Park. By 1986, this leads to a DNA polymerase that can amplify tiny amounts of DNA, a powerful tool for courts and biologists alike.

1987 - November 24

NSF announces the awarding of the NSFNET Cooperative Agreement to Merit, IBM and MCI. With additional support from the state of Michigan, the agreement will result in the building of a new, high-speed NSFNET backbone, the foundation for the internet.

1990s

For decades, NSF has supported informal STEM education, including such fun and innovative television shows as the "The Magic School Bus" to which NSF committed support in 1991.

1990s

Computer visualization techniques, such as computer graphics, animation and virtual reality, are pioneered with NSF support. Weather patterns, medical conditions and mathematical relationships are only some of the uses to which virtual reality can be applied.

1990s

Since the development of functional magnetic resonance imaging, a kind of MRI, in the early 1990s, NSF has supported numerous fMRI studies that have resulted in a deeper understanding of human cognition and brain function across a spectrum of areas.

1990s

Qualcomm revolutionizes cellphone technology with CDMA wireless technology and becomes a Fortune 500 company. In the 1980s, Qualcomm received two grants from NSF's Small Business Innovation Research program.

1991

NSF-funded researchers at Penn State University discover the first of three extra solar planets using radio telescopes. Two of these planets are similar in mass to the Earth. The third has roughly the mass of the moon.

1991 - March 4

Walter E. Massey becomes director of NSF (1991–1993).

1991 - October 24

NSF's new Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences is announced.

1992

Two sites for the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory are announced, one at Livingston, Louisiana, and one at Hanford, Washington.

1992

The Big Bang theory is confirmed. For this 1992 discovery of the basic form and small variations in the cosmic microwave background radiation, NSF-funded researcher George Smoot of the University of California, Berkeley will share the 2006 Nobel Prize in physics with John Mather of NASA.

1993

NSF-funded Andrew Wiles presents the first and only novel proof of mathematician Pierre de Fermat's deceptively simple proposition he called his "last theorem." This contributes to secure communications and cryptography.

1993

NSF-funded scientists detect volcanic eruptions on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. By using U.S. Navy hydrophone arrays, oceanographers can monitor in real time volcanic eruptions on the ridge. NSF supports these and other technologies and their applications to volcanoes.

1993 - October 7

Neal F. Lane is confirmed as director of NSF (1993–1998).

1994

NSF joins the Department of Defense and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in funding new technologies for digital libraries, making more information available over the internet.

1994 - August 24

NSF announces the Advanced Technological Education program, an effort to improve the education of technicians in technologically advanced fields such as gas metal arc welding.

1998

Two teams of NSF-supported astronomers discover that not enough matter exists to slow the universe's expansion. Instead, a mysterious force — dark energy, which accounts for almost three-fourths of the universe's mass-energy — expands it at an increasing rate (2011 Nobel Prize in physics).

1998 - May 22

Rita R. Colwell is confirmed as director of NSF (1998–2004).

1998 - September 28

NSF announces major support for plant genome research, including important crops like corn, soybeans, tomatoes and cotton. This follows a multi-agency, multinational, decadelong effort to sequence and locate every gene in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

2000 - October 31

Responding to the White House Initiative on Tribal Colleges and Universities, NSF provides grants through the new Rural Systemic Initiative to improve science, mathematics and technology education in K-12 schools on tribal reservations.

2001

With NSF funding, physicists and ophthalmologists at the University of Michigan develop a procedure with an ultrafast laser for improved LASIK eye surgery. They make significant improvements to interventions in both laser microsurgery and LASIK eye surgery.

2001

With a new push to improve education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, NSF coins the STEM acronym, replacing the less easily said SMET.

2001 - September 19

NSF establishes six major centers for nanoscale science and engineering research. With nanotechnology as a cross-disciplinary approach to science and engineering of the very small, NSF invests effectively in diverse researchers and new collaborations.

2003

NSF establishes a Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems Engineering Research Center. These use fundamental principles in biology to develop novel science and engineering based on nature, with a goal to create new machine-human interfaces for the understanding and treatment of disease.

2004

Breakthroughs lead to the new field of optogenetics, a research technique that enables scientists to use light to precisely control the activity of individual cells within living tissues, effectively turning them "on" or "off." In 2010, this technique was named the "Method of the Year" by the journal Nature Methods.

2004 - November 24

Arden L. Bement Jr. is sworn in as director of NSF (2004–2010).

2005

With funding from the Partnerships for International Research and Education program, U.S. and African scientists study the largest geophysical anomaly inside the Earth: the African Superplume, a huge mass of hot rock rising from the core-mantle boundary.

2007

Advances in remote, real-time, speech-to-text translation (C-PRINT) allow NSF-funded researchers to develop inexpensive smartphone technology to improve communication between hearing professors and deaf or hard-of-hearing students in lab and field classes.

2007

The South Pole Telescope — the largest radio telescope ever built in Antarctica — collects its first observations. The telescope stands 75 feet tall, is 33 feet across and weighs 280 tons.

2008 - October 8

The discovery and development of green fluorescent protein, an amazingly useful tool that allows scientists to track cellular processes, is recognized with the Nobel Prize in chemistry. NSF supported research on this jellyfish protein beginning in the 1960s and supported all three of the Nobel laureates.

2009

An international team of scientists announces its discovery and reconstruction of a fairly complete skeleton of the hominid Ardipithecus ramidus, dating to 4.4 million years ago. Nicknamed Ardi, the female skeleton is 1.2 million years older than the skeleton of Lucy.

2010

NSF-supported researchers use economic matching theory to develop a kidney exchange program that dramatically improves efficiency and doctors' ability to match organs. For his work in this area, Alvin Roth shares the 2012 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

2010 - September 29

Subra Suresh is confirmed as NSF director (2010–2013).

2011

NSF solicits proposals for its part of the multiagency National Robotics Initiative to accelerate the development and use of assistive robots. NSF has since supported research in robotics in such burgeoning areas as search-and-rescue and reconnaissance, for example.

2011 - July 28

NSF announces the new Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program to move from discoveries to process or product. These public-private partnerships bring together NSF-funded researchers with entrepreneurs and businesses.

2012

A natural immune system found in many bacteria is characterized and repurposed as a powerful new biological tool: CRISPR. NSF-funded researchers develop the new technique that enables the rewriting of specific genetic information.

2012

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN announces the detection of the Higgs boson, a long-predicted subatomic particle. NSF had supported approximately 400 scientists at U.S. universities who had participated in LHC experiments and specifically helped to design, build and operate the particle detectors.

2013

The R/V Sikuliaq, the NSF-funded, next-generation arctic sea vessel, is launched. It supports dozens of researchers with onboard laboratories and specialized deck equipment, enabling multidisciplinary studies in high latitude open seas and near-shore regions.

2013 - April 2

The White House announces an initiative called Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies. The BRAIN Initiative is an effort by federal agencies and private partners to support and coordinate research to understand how individual brain cells and complex neural circuits interact at the speed of thought.

2014 - March 12

France A. Córdova is confirmed as NSF director (2013–2020).

2015

In 2015, the National Ecological Observatory Network begins operation. A precedent-setting, multidisciplinary infrastructure, NEON generates snapshots of ecosystem health by measuring ecological activity in strategic locations throughout the U.S.

2016

An NSF-funded researcher develops a tool that examines a child's brain waves and can predict reading problems, such as dyslexia, before they appear. This is important because health interventions for children are most effective when they begin early.

2016

As part of NSF's Quantum Leap Big Idea and to secure communication, NSF's Office of Emerging Frontiers and Multidisciplinary Activities awards $12 million to develop systems that use photons in pre-determined quantum states to encrypt data.

2016 - February 11

NSF and the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory announce the direct observation of gravitational waves resulting from merging black holes approximately 1.3 billion light-years away. LIGO confirms a major prediction of Einstein's general theory of relativity (2017 Nobel Prize in physics).

2016 - May

NSF unveils 10 Big Ideas intended to shape new areas of research, address critical gaps in the nation's research enterprise and tackle grand challenges of a scientific or societal nature.

2016 - September

NSF issues the first awards for NSF INCLUDES (Inclusion across the Nation of Communities of Learners of Underrepresented Discoverers in Engineering and Science), which aims to improve access to STEM education.

2018 - July 12

NSF's IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica, verified by ground- and space-based telescopes, produces the first evidence of a source of high-energy cosmic neutrinos, answering a century-old astrophysics question with new multi-messenger tools.

2018 - September

NSF announces new measures to protect the research community from harassment, publishing new terms and conditions for awardees. NSF leads the way in addressing this problem in order to promote safe, productive research and education environments for current and future scientists and engineers.

2019

The White House issues "Executive Order on Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence." Funding AI research since the early 1960s, NSF is a central player, with earlier breakthroughs in disaster predictions, medical procedures and more.

2019 - April 10

The Event Horizon Telescope project and NSF hold a press conference to reveal the first image of a black hole. EHT scientists captured the image, outlined by hot gas emissions swirling near its event horizon.

2020 – June 18

Sethuraman Panchanathan confirmed as director.

2022 – March 16

NSF establishes the Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships — its first new directorate in 30 years — to bridge curiosity-driven and use-inspired research and grow industry, create new jobs, and cultivate an equitable STEM workforce across the nation.

2022 - May 12

NSF, with the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, hold a press conference to unveil the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

NSF's directors

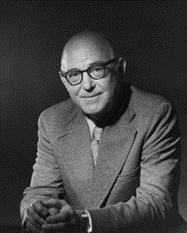

The first director of the National Science Foundation served two full terms from April 1951 through June 1963. "A quiet individual, a real scholar and decidedly effective in his quiet way, for everyone likes him and trusts him," was the way Vannevar Bush described Alan Waterman. Detlev Bronk, who chaired the National Science Board during Waterman's years as director, thought he was a "kind and gentle" man, but also someone who could be "firm and exacting...and persistent in the fulfillment of his duties."

Educated at Princeton University, Waterman received his Ph.D. in physics in 1916. After graduation, he taught physics at the University of Cincinnati. During World War I, his academic career was interrupted by two years with the Science and Research Division of the Army Signal Corps. He then returned to teaching, at Yale University, until the outbreak of World War II. His career with the government during the war included service with the National Defense Research Committee and the Office of Scientific Research and Development. In August 1946, he became deputy chief and chief scientist of the Office of Naval Research.

Waterman shaped NSF, starting with the decision to award grants rather than contracts and the use of panels of non-NSF scientists and engineers to provide advice to the staff on the quality of proposals. During his tenure as director, NSF's budget rose from $3.5 million to more than $320 million.

The second director of the National Science Foundation served one full term from July 1963 through June 1969. According to Leland Haworth's biographers, his "traits of objectivity, attention to detail and sensitivity to the problems and concerns of others" were what made him such an influential science administrator. Staff who worked under him thought that the "key to the man's character was integrity."

After earning his A.B. and A.M. from Indiana University, Haworth received his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Wisconsin in 1931. He began teaching at Wisconsin, where he remained until 1937, when he received a fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The following year he moved to the University of Illinois, where he officially remained until 1947, although he spent World War II at the MIT Radiation Laboratory doing research on airborne interception radar. He left Illinois to become assistant director at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, and in October 1948, became director. President John F. Kennedy appointed him a member of the Atomic Energy Commission in 1961.

Although continuing many of the priorities of NSF's first director, Alan T. Waterman, Haworth took the first major steps to increase NSF's role in applied research and technology. During his tenure, the NSF budget rose to a peak of over $505 million in fiscal year 1968. The following year, however, the impacts of the war in Vietnam and the costs of the Great Society took their toll on the NSF budget, and funding was reduced to $433 million, the first such reduction in the history of NSF.

The third director of the National Science Foundation was the first biologist and the first not to complete his full term. William McElroy served from July 1969 through January 1972, although he announced his intent to depart in July 1971. Colleagues praised his ability to communicate with laymen, including politicians, about the value of science. He was also known for his ability "to admit when he is wrong."

He received his B.A from Stanford University in 1939, his master's from Reed College in 1941 and his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1943. After graduation, McElroy worked for the Office of Scientific Research and Development. In 1945, he had a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford. The following year he joined the faculty at Johns Hopkins University, where he remained until coming to NSF. His research at Johns Hopkins focused on luminescent organisms and he was known for his work on the biochemistry of fireflies.

McElroy was a controversial director. Unlike his predecessors, he was an aggressive lobbyist for NSF and for science in general. During his short term as director, he managed to increase NSF's budget by almost 50%. Much of the increase, however, was in support of large-scale applied research, including the program Research Applied to National Needs (RANN). Some felt he was radically changing the thrust of the foundation. Also controversial was his decision to bring in professional administrators from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The fourth director served from February 1972 through August 1976. The first National Science Foundation director to have a background primarily in engineering, H. Guyford Stever attempted to expand NSF's role in applied research while still defending the importance of basic research. Steering a middle ground in turbulent times, he wrote early in his tenure that "science has got to come to grips with the current problems of the Nation and society," while acknowledging that the primary mission of NSF was "to strengthen the basic sciences." As the citation for the Vannevar Bush Award in 1997 noted, "in the most divisive and controversial times, he has been our voice of reason, wisdom, and insight — our sage of science."

Stever received his undergraduate degree from Colgate University and his Ph.D., in 1941, from the California Institute of Technology, with a thesis on the lifetime of the mason, a subatomic particle. During World War II, he conducted research at the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and served as science liaison in Europe for the Office of Scientific Research and Development. He joined the faculty of MIT in 1946 and remained there until 1965, when he became president of Carnegie Mellon University. He was president of Carnegie Mellon and a member of the National Science Board when he was selected to be NSF's director.

When President Richard M. Nixon abolished the President's Science Advisory Committee and the Office of Science and Technology, effective July 1, 1973, responsibility for serving as science advisor to the president was given to the director of NSF. Stever held the dual positions of presidential science advisor and director of NSF until he was nominated by President Gerald R. Ford to be the first director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy and presidential science advisor in 1976.

Stever's tenure as director was marked by two controversies. The first was over the program Research Applied to National Needs (RANN), which members of the scientific community felt was draining funds from basic research. The other was over "Man: A Course of Study," a social science curriculum for middle-school students which raised issues about normative family values, upsetting social conservatives in Congress.

"We are living in one of history's most productive eras of intellectual discovery. From agriculture to medicine, from aerospace to computing, science is experiencing a series of revolutions that are remaking our idea of what is possible. These revolutions are occurring on the campuses and laboratories of research universities every day."

– Richard C. Atkinson, October 1999

Richard C. Atkinson served as the fifth director of the National Science Foundation, from May 1977 to June 1980. Atkinson assumed the position of director already well versed in the challenges of leading the only federal agency dedicated to the support of basic research and education in all fields of science and engineering. He was the first director to have served as deputy director (from 1975 to 1976), and he also served as acting director from August 1976 to May 1977 upon the departure of H. Guyford Stever. As an internationally recognized experimental psychologist and applied mathematician, Atkinson was the first NSF director with a background in social science. In the face of vocal critics in Congress and the media, Atkinson defended NSF's commitment to basic research. During his tenure as director, he negotiated a historic scientific exchange between the United States and the People's Republic of China and strengthened NSF's peer review process.

Before NSF

Atkinson earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago in 1948 and his Ph.D. in psychology from Indiana University in 1955. After serving in the U.S. Army, Atkinson joined the faculty at Stanford University in 1956.

In 1957, after a year of lecturing in the Applied Mathematics and Statistics Laboratories at Stanford, Atkinson moved to the University of California, Los Angeles. From 1961 to 1980, he served on the faculty at Stanford in the department of psychology. Atkinson's research on mathematical models of human memory and cognition gained him international recognition and led to the development of computer-controlled instructional systems aimed at addressing problems of learning in the classroom. Atkinson's innovative research also led to joint faculty appointments in Stanford's School of Engineering, School of Education, and Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences.

While at Stanford, Atkinson held various academic and professional leadership positions. From 1961 to 1975, Atkinson served as associate director of the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences and from 1968 to 1973 as chairman of Stanford's department of psychology. Among other positions, Atkinson served as editor of the Journal of Mathematical Psychology (1963 to 1970), on the editorial board of Psychological Review (1966 to 1968), on the board of directors of the American Psychological Association (1973 to 1976), and as president of the American Psychological Association's Division of Experimental Psychology (1974 to 1975).

Director of NSF

In 1975, President Gerald Ford appointed Atkinson as deputy director of the National Science Foundation. A year later, in 1976, President Jimmy Carter appointed him to the position of NSF director. Atkinson served as acting director until in May 1977 he was confirmed as director by the Senate.

As Director, Atkinson presided over NSF's first $1 billion annual budget. His tenure at NSF began in the midst of controversy and public criticism of various foundation-funded research projects and education curricula (such as "Man: A Course of Study"). At a time when the foundation was under heightened scrutiny, Atkinson did much to improve NSF relations with Congress and strengthen the process of peer review at NSF. His predecessor as director, H. Guyford Stever, later commended Atkinson for his leadership during this period, praising his "wide grasp of issues" and "breadth of knowledge."

Atkinson made history by negotiating the first memorandum of understanding between the United States and the People's Republic of China, which opened the door for major exchanges of scientists and scholars between the two nations. His efforts contributed to a comprehensive agreement between China and the United States on science and technology that was signed in January 1979 by Chairman Deng Xiaoping and President Carter.

Atkinson recognized that the clustering of research grants among the top universities negatively impacted NSF's ability to gain broad support in Congress. Under Atkinson's leadership, NSF initiated a program aimed at broadening the geographical distribution of research grants. Established during his tenure and still in existence today, the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR, known as "Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research" as of January 2017) provided a framework for helping universities in states that received few research grants by providing them with advice about developing more competitive grant applications.

After NSF

When Atkinson left NSF in 1980, he became chancellor at the University of California, San Diego, leading the university through its biggest growth period. During his 15-year tenure as chancellor, UC San Diego rose to "top five" status in acquiring federal research funding and was ranked among the top ten graduate programs in the United States by the National Research Council. In 1995, Atkinson became the University of California system's 17th president, a position he held until 2003. During this period, Atkinson initiated national reforms in college admissions testing and spearheaded new approaches to admissions and outreach in the post-affirmative action era at the university system. Atkinson now holds the title of president emeritus of the University of California and professor emeritus of cognitive science and psychology at UC San Diego.

Atkinson has received many awards and honors throughout his distinguished career. In 1974, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the National Academy of Education. In 1989, he served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In 2003, he won the National Science Board's prestigious Vannevar Bush Award, an award he established in 1980 during his tenure as director, for his lifetime contributions to the nation in science and technology. Atkinson also has the distinction of having a mountain in Antarctica named in his honor.

“The challenge to the foundation is to create a flexible structure that can accommodate creativity in both the search for new knowledge and the seizing of exciting and useful opportunities to apply it. This is not something we expect to do by the mere shifting of organizational boxes or reallocation of dollars. It involves a subtle but fundamentally significant broadening of perspectives on the part of those throughout the science and engineering communities who have been accustomed to think in terms of science versus engineering or basic versus applied research.”

– John B. Slaughter, January 3, 1981

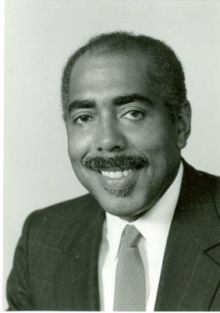

John Brooks Slaughter served as the sixth director of the National Science Foundation from December 1980 to October 1982. Slaughter, the first African American to be appointed as NSF director, was a strong advocate for the inclusion of women and minorities in science and engineering. He frequently expressed concern about the "stagnation that appears to have occurred in science education" and stressed engineering education and support for minorities and women in science as important priorities.

Prior to his appointment as director, Slaughter served (1977 to 1979) under NSF Director Richard Atkinson as assistant director for the Astronomical, Atmospheric, Earth and Ocean Sciences directorate. He considered this service to have been "a tremendous learning experience."

Early life, education and training

Slaughter attended an all-Black elementary school in then racially segregated Topeka, Kansas, but later attended a racially-mixed high school. He developed a keen interest in electrical engineering at an early age and built electronic devices as a hobby. He transformed this hobby into a radio repair shop when he was in high school, a home business that helped finance his higher education.

He earned a B.S. in electrical engineering from Kansas State University in 1956 and a master's in engineering from University of California, Los Angeles in 1961. Slaughter obtained a Ph.D. in engineering science, also known as engineering physics, from the University of California, San Diego in 1971.

Before NSF

Slaughter took his first position in 1956 as electrical engineer with General Dynamics Corporation and moved to San Diego in 1960 to become head of information systems technology at the U.S. Navy Electronics Laboratory. In 1975, he accepted an offer from the University of Washington as director of the Applied Physics Laboratory and professor of electrical engineering. He held this position until 1977 when he joined NSF as an assistant director. Slaughter returned to academia in 1979 as academic vice president and provost at Washington State University. He was in this position for about a year when he received a call from President Jimmy Carter, urging him to accept the nomination as director of NSF.

Director of NSF

Slaughter assumed the position as NSF director as outgoing President Carter signed into law an appropriations bill for NSF that provided support for bringing women and minorities into full participation in science and engineering. Despite this positive start for the new director, Slaughter immediately faced a major crisis. The administration of newly elected President Ronald Reagan directed NSF to terminate support for science education as well as the behavioral and social sciences programs.

As generally expected of the NSF director, Slaughter was to defend the president's budget at the annual authorization hearing of the Subcommittee on Science, Research and Technology of the House Science and Technology Committee. Slaughter instead made the daring decision to publicly disagree with the administration's directive by emphasizing the need for NSF to continue support for science education and the social sciences. “It satisfied me that I had been honest,” he said in a 2007 interview. “It also indicated to me that my time at NSF was going to be short; I could not support the president's request.” Except for graduate fellowships, which the agency continued to award, the NSF budget supporting science education was terminated, along with support for the social sciences.

Slaughter considered these budget cuts an opportunity for creative reorganization that would enable continued support for the affected areas. This was accomplished by eliminating the Directorate for Science and Engineering Education and replacing it with the Office of Scientific and Engineering Personnel and Education. This recasting enabled NSF to remain engaged in science education as well as minority inclusion efforts.

Slaughter also believed that engineering needed to receive more attention than it did and that its increased visibility and expanded role, as a scientific endeavor, would be an asset to NSF and the nation. He built on earlier focus on this issue and groundwork laid by his predecessors to propose, develop and establish NSF's engineering directorate.

Another major concern for Slaughter was what he perceived as a poor relationship between NSF and scientists from predominantly minority institutions. He noted that these scientists believed there was a presumption on the part of NSF that their research did not measure up to research from predominantly white universities. Slaughter therefore actively worked to encourage submission of research proposals from historically Black colleges and universities. He visited several of these institutions to present the values of NSF. “There had grown a sense of alienation that needed to be addressed” he said in the 2007 interview.

After NSF

Slaughter left NSF in 1982 to become chancellor of the University of Maryland, College Park, where he served until 1988, when he became president of Occidental College, the first Black person to hold that position in the 100-year history of the college. He left Occidental in 1999 to become the R. Melbo Professor of Leadership in Education at the University of California, Irvine. In 2000, he accepted an offer as president and CEO of the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering, Inc., an organization that inspires excellence in engineering education for women and minorities. Slaughter also held a joint appointment as professor emeritus of education and computer engineering at the University of Southern California's Rossier School of Education and Viterbi School of Engineering.

Slaughter passed away in Pasadena, California, on Dec. 6, 2023.

“The Foundation will support the best possible research in the best possible manner within its resources. Wherever outstanding researchers may be, they will be funded at levels needed to perform their research. Our funding actions will accord with our goal to attract the very best minds in the nation to scientific research, and to provide them with excellent training.”

– Edward A. Knapp, January 6, 1983

Edward A. Knapp was the seventh director of the National Science Foundation and served from November 1982 to August 1984. Early in his tenure as director, Knapp expressed concern that American preeminence in science was "in trouble because we no longer have enough excited, enthusiastic graduate students and postdoctoral fellows" in the sciences. He also noted that scientific instruments in most universities were obsolete. NSF policy, he declared, would be to engage the educational system in attracting and producing top quality scientists and equipping scientists with the tools they needed to attain scientific excellence.

Knapp's first appointment to NSF was as assistant director of the mathematics and physical sciences directorate, nominated by President Ronald Reagan in July 1982. He served in this role between September and November of that year, before his appointment as NSF director.

Early life, education and training

Knapp was born in Salem, Oregon, and did his undergraduate studies at Pomona College in Claremont, California, receiving a B.A. in 1954. He earned a doctorate in physics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1958, where he conducted research on elementary particles using Berkeley's electron synchrotron.

Before NSF

Knapp joined the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in New Mexico in 1958, where he began his distinguished career. In 1971, he became associate division leader for the Medium Energy Physics Division.

He contributed to the establishment of the Clinton P. Anderson Meson Physics Facility, a high-current accelerator that opened new opportunities in multiple areas including nuclear physics research and radiotherapy. Upon completion of the biomedical wing of the facility in 1972, Knapp participated in a collaborative program to explore the utility of negative pions in radiotherapy — heavy ionizing particles that could offer greater selectivity in cancer treatment.

Knapp established the Accelerator Technology Division at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in 1976 and was promoted to division leader in 1978. He was a guest scientist in 1978 in the USA-USSR Exchange program in Fundamental Properties of Matter and in 1979 in the US-Japan Cooperative Cancer Research Program.

Director of NSF

Knapp's assumption of duty as NSF director was marked early on by controversy, as he immediately asked for the resignations of three assistant directors, previously appointed by former president Jimmy Carter. Fears in the scientific community of political control and intervention were allayed, however, as he declared his intent to support strong basic research, rebuild precollege science education programs at NSF, increase support for undergraduate science education and promote international research collaboration.

Knapp established the first NSF young faculty fellowship program in 1983. The Presidential Young Investigator program provided funding to promising young tenure-track faculty to support their research for five years. The goal of the program was to improve the capacity of higher institutions to produce highly qualified scientists and engineers for academic and industrial research, and to encourage research partnerships between young faculty and the private sector.

In 1982, in collaboration with the Department of Defense, NSF convened a panel of experts, chaired by Peter D. Lax of the National Science Board, to assess the needs for large-scale computing in the country. In its report of December 1982, the panel recommended that a program be established "to stimulate exploratory development and expanded use of advanced computer technology" with the objective of establishing supercomputer networks that linked academic, government and private-sector scientists and engineers. This laid the foundation for the establishment in 1985 of the NSF supercomputer centers.

Another significant accomplishment during Knapp's tenure as NSF director was the launch of the Engineering Research Centers program. In February 1984, NSF convened a panel of the National Academy of Engineering to advise on the organization and mode of operation of the centers. In its report to Knapp, the panel described its vision of the engineering research centers as entities conducting research across disciplines of science and engineering toward the goal of greater competitiveness of U.S. industry, while educating engineers at all levels. The report established the foundation for the Engineering Research Centers program with the first generation of centers launched in 1985.

During a difficult period for the NSF budget, Knapp oversaw an increase in appropriations. The NSF budget request for 1982 was cut by 23%. This led to a scuttling of programs in science education and behavioral sciences. Under Knapp, however, NSF budget appropriations grew to $1.34 billion in 1984, a 35% increase over 1981 appropriations, enabling the re-establishment of key programs in science education.

After NSF

Knapp returned to the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in late 1984, citing his desire to remain a researcher rather than an administrator as the main reason for leaving NSF. From 1985 to 1989, he was president of Universities Research Association Inc., a consortium of universities that operate certain national research facilities, including Fermilab. From 1989 to 1991, he served as director of Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility and from 1991 to 1995 as president of the Santa Fe Institute, a private organization that promotes interdisciplinary research.

Knapp passed away in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on Aug. 17, 2009.

"Above all, the NSF needs to be alert to the changes that affect the country's competitiveness, the innovations that will be the breakthrough of tomorrow — and must support these ideas, no matter their origin, in a timely manner and with ample resources, if it is to make a difference."

– Erich Bloch, February 20, 2010

On Aug. 6, 1984, the Senate confirmed President Ronald Reagan's appointment of Erich Bloch as the eighth director of the National Science Foundation. Bloch, the first NSF director with industrial research and no academic background, believed NSF-supported research must be linked to economic development. He saw research as a highly competitive field and "no more international than commerce."

Bloch was the second of only two directors to serve a full six-year term as NSF director. During his term, the agency transitioned from supporting only purely academic research to including applied research in its portfolio. His strong advocacy for research as an important activity for maintaining national competitiveness led to an increase in government funding to NSF from $1.3 to $2 billion during his tenure.

Early life, education and training

Bloch was born on Jan. 9, 1925 in Sulzburg, Germany. He lost his parents during the Holocaust and survived World War II in a home for young refugees in Switzerland. He studied electrical engineering for two years at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) before emigrating to the U.S. in 1948. He continued his studies in electrical engineering at the University of Buffalo, now the State University of New York at Buffalo, and obtained a bachelor's degree in 1952.

Before NSF

After graduation, Bloch joined IBM as an electrical engineer in the company's Poughkeepsie, New York, laboratory and later became engineering manager of the IBM 7030 supercomputer. In 1962, he led the Solid Logic Technology program team in developing the microelectronic technology used in the IBM System/360 supercomputer. System/360, announced in 1964, was the first mainframe computer built with the 8-bit architecture that revolutionized the computer and data processing industry. Bloch received a National Technology Medal in 1985 for his contribution to this innovation.

Bloch became general manager of IBM's East Fishkill, New York, facility in 1975 and a year later, vice president of the Data Systems Division. In 1981, he assumed responsibility as head of the corporate technical personnel development staff and was subsequently named corporate vice president of IBM.

Director of NSF

As director of NSF, Bloch eschewed what he viewed as a false dichotomy between science and technology and urged a full integration of science and engineering research at NSF. He argued that the agency's emphasis on research ideas generated by individual investigators had left the agency unresponsive to national goals. Bloch reasoned that multidisciplinary research would yield transformative discoveries and strengthen national economic competitiveness. To this end, NSF established Engineering Research Centers in several universities and Science and Technology Centers or Integrative Partnerships to promote multidisciplinary research.

Science and Technology Centers involve diverse science and engineering disciplines from academic institutions, partnering with national laboratories and industry to integrate education and research toward development of novel technologies. The ultimate objective of these centers is to invent and spin off new technologies into businesses while also producing science and engineering graduates.

To emphasize computer science, Bloch consolidated existing computer science programs housed in disparate areas of NSF — such as engineering, economics and mathematics — into a new computer and information science and engineering directorate, with a mission to uphold the nation's leadership in computer science. The new directorate funded the establishment of five supercomputer centers around the country and in 1986 linked them to create a wide area network, the NSFNET, which enabled scientists and engineers to access supercomputing capacity across the country. The NSFNET served as the original backbone and progenitor of the modern internet.

Bloch also initiated a revision of NSF merit review, a rigorous peer-review system for evaluating, ranking and selecting research grant applications for NSF support. While this system was the global gold-standard for reviewing research proposals, it was generally deemed too conservative and risk-averse. Bloch proposed a modification that would enable support of promising research, considered high risk by the merit review, with small and time-limited grants, at the discretion of the program manager. This idea eventually resulted in the Small Grant for Exploratory Research program, supporting preliminary research on untested and risky ideas or those involving severe urgency.

After NSF

After leaving NSF in 1990, Bloch joined the Council on Competitiveness in Washington, D.C., as its first distinguished fellow and became a distinguished visiting professor at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. For his contributions to the advancement of science and technology, he was honored by the National Science Board in 2002 with the prestigious Vannevar Bush Award. Erich Bloch passed away on Nov. 25, 2016 at the age of 91.

"Although it sometimes appears to be dèjá vu all over again, the NSF and the nation have learned from the past and the NSF is remarkably resilient and adaptable. Its commitment to a set of core principles — excellence above all, listening to and taking directions from practitioners not just bureaucrats and continually renewing itself, bringing in fresh talent to the organization and to the fields it supports — will sustain it in the future."

— Walter E. Massey, February 20, 2010

Walter E. Massey was appointed the ninth director of the National Science Foundation by President George H. W. Bush in 1991, the 40th anniversary year of the foundation. He served from March of that year to April 1993. Massey strongly believed in improving the quality of science education and boosting the amount of technical and scientific education at all levels, especially for minorities and women. He challenged NSF to support the exploration of the best methods of teaching science, not only at the graduate level, but also from K-12 through undergraduate education.

Massey had affiliations with NSF before becoming director. He was a recipient of an NSF grant in science education during his academic career and served on three NSF advisory committees: Physics, Science and Engineering, and International Programs. Massey became a member of the National Science Board in 1978 and served until 1984.

Early life, education and training

Massey was born on April 5, 1938 in then racially segregated Hattiesburg, Mississippi. While in tenth grade, Massey passed an early entry examination for Morehouse College and began his college education at the age of 16 with a Ford Foundation fellowship. He obtained a B.S. degree in 1958 and a doctorate in physics from Washington University, St. Louis in 1966. He pursued postdoctoral training in theoretical physics from 1966 to 1968 at the University of Chicago-affiliated Argonne National Laboratories.

Before NSF

In 1968, Massey was appointed assistant professor of physics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. As one of four Black faculty on a faculty of more than 5,000, Massey felt a strong need to promote science education for minorities, and he actively engaged in the recruitment, tutoring and counseling of Black students at the university.

He left the University of Illinois in 1970 to join Brown University as an associate professor and was promoted to full professor in 1975. While at Brown, Massey established the Inner-City Teachers of Science program in Providence, Rhode Island, supported by NSF funding. The mission of the program was to train inner-city science teachers in the latest methods of science education as an approach to promoting science in minority high schools.

In 1979, Massey returned to Argonne National Laboratories as its sixth director, with a joint appointment as professor of physics at the University of Chicago. This was a time in which Argonne's mission as a nuclear energy research facility was facing severe skepticism due to the partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant on March 28 of that year. Massey worked against the odds to restore funding for nuclear energy research and re-branded Argonne as a visionary scientific research institution.

Director of NSF

Immediately following his appointment to the directorship of NSF, Massey advised the National Science Board to set up a commission to consider the future of NSF in the face of a changing world. The board accordingly set up a 15-member Commission on the Future of the National Science Foundation, which on Nov. 20, 1992, issued a report entitled "A Foundation for the 21st Century: A Progressive Framework for the National Science Foundation." The report reaffirmed the primary mission of NSF to support first-rate research initiated by individuals in the scientific community to probe the frontiers of science in the search for new knowledge. It also advised that resources be deployed toward "strategic areas in response to scientific opportunities that meet national goals." The report concluded that the National Science Board must work with the private and public sectors to formulate a national science and technology roadmap.

Another one of Massey's notable achievements was the establishment of the Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences. The directorate supports basic research on human behavior and social organizations and how social, economic, political, cultural, and environmental forces affect the lives of people from birth to old age and how people in turn shape those forces. The premise for Massey's support of this area of research is that novel insights into developmental sciences can lead, among other things, to new approaches toward child education and development.

Massey was also instrumental in the development of the advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory, which enabled scientists to record for the first time in February 2016 the existence of gravitational waves as predicted 100 years earlier by Einstein's general theory of relativity. Work on LIGO began in 1980. Requests for adequate funding for LIGO were, however, routinely rejected throughout the 1980s, amid lingering doubts about its technical feasibility and administrative organization. It was not until 1992, during Massey's tenure as NSF director, that adequate funding was approved for the project, leading to its eventual success.

After NSF

Massey left NSF in 1993 to serve as provost and vice president for the 10-campus University of California system, where he remained until 1995, when he returned to his alma mater, Morehouse College, as president. In 2010, he joined the School of the Arts Institute of Chicago as president and is currently its chancellor.

"We in the science and engineering community know that we can no longer expect to plan the full research agenda solely within the circle of our own community. On the other hand, planning the science agenda without the active participation of scientists and engineers will create disappointing results all around. Thus, the role of the civic scientist becomes a critical and integral part of developing a new science agenda for a post-Cold War world."

– Neal F. Lane, February 13, 1998

Neal F. Lane served as the 10th director of the National Science Foundation from October 1993 to August 1998. A physicist and strong supporter of improving communication between the scientific community and the general public, Lane encouraged scientists to create dialogue with fellow citizens about the importance of science and its ability to meet various social needs. Lane assumed the NSF directorship already well-versed in the inner workings of the agency, having served as assistant director of NSF's Division of Physics from 1979 to 1980 and as a participant in several NSF advisory panels.

During his five-year tenure as NSF director, Lane oversaw the establishment of new programs designed to integrate research and education, the creation of an agencywide effort to harness the power of emerging technologies such as the internet and supercomputing for science and education, and a substantial increase in funds for modernizing scientific research equipment and infrastructure.

Before NSF

Lane earned his bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees from the University of Oklahoma. After completing his Ph.D. in 1964, Lane received an NSF postdoctoral fellowship to study at Queens University in Belfast, Northern Ireland for a year. In 1965, Lane continued his research in theoretical atomic and molecular physics at the University of Colorado Boulder's Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics, or JILA, as a visiting fellow.

After a year at JILA, Lane joined the physics department faculty at Rice University. In 1967, Lane took a leave of absence from Rice to conduct research at Oxford University as an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation fellow. In 1979, after being promoted to professor of physics, space physics, and astronomy at Rice, Lane took a second leave of absence to serve for a year as director of the Division of Physics at NSF. Lane remained at Rice until 1984, when he accepted a position as chancellor at CU Boulder. In 1986, after two years at CU Boulder, Lane returned to Rice as provost, a position he held until his appointment as NSF director in 1993.

During his time at Rice and CU Boulder, Lane held numerous leadership positions within the scientific community and received several teaching awards. An active member of the American Physical Society, Lane chaired the APS Division of Electron and Atomic Physics from 1977 to 1978 and served on the Executive and Finance Committees from 1981 to 1983. He served on the National Research Council's Committee on Atomic and Molecular Sciences from 1980 to 1984 and chaired the NSF Advisory Panel on Advanced Scientific Computing from 1984 to 1986. Recognized for his teaching excellence at Rice, Lane received the George R. Brown Prize for Superior Teaching in 1973 and 1976.

Director of NSF

On Oct. 15, 1993, Lane was sworn in as NSF director during a period of transition for the agency. Growing concerns over the ballooning federal deficit called into question Cold War-era justifications for the urgency of federal support for basic scientific research. As director, Lane played a vital role in defending the agency against projected budget cuts by emphasizing the importance of NSF-funded science in strengthening the American economy and securing global leadership. Through his leadership and communication of the benefits of scientific discovery to wider audiences, NSF refined its merit review process for funding grant proposals by adding two new criteria: intellectual merit and broader impact.

Concerned with how best to educate and prepare students to face the challenges of a rapidly changing scientific and technological landscape, Lane directed funds toward agency programs designed to immerse students in a "discovery-rich environment" through integrating education and research. Lane increased funds for the Research Experiences for Undergraduates program and the Grant Opportunities for Academic Liaison with Industry program (GOALI), which granted opportunities for graduate students and post-docs to work in industrial settings. In 1998, NSF launched a new program called Integrative Graduate Education and Research Training aimed at broadening graduate education in science and engineering by funding students to study in multidisciplinary settings with opportunities for collaboration with industry researchers.

Lane also initiated an NSF-wide venture known as Knowledge and Distributed Intelligence, or KDI, to address the impacts of advances in computing power and networking tools on science and engineering research and to encourage and direct future innovations and applications. Cutting across all fields of research at NSF, KDI supported multidisciplinary approaches to studying knowledge-based networking, learning and intelligent systems, and new approaches to computation tools. KDI also provided funds for NSF's role in a federal, multi-agency effort to increase the speed and networking functionality of the internet known as the Next Generation Internet program.

After NSF

Though his tenure as NSF director ended in 1998, Lane's work in directing federal science policy continued. From 1998 to 2001, Lane served as assistant to the president for science and technology and director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy in President Bill Clinton's administration. In 2001, Lane returned to Rice after a distinguished career in federal service. He is currently a Senior Fellow in Science and Technology Policy at Rice University's Baker Institute of Public Policy and also holds the titles of Malcom Gillis University Professor Emeritus and Professor Emeritus of Physics and Astronomy. Lane has won numerous awards, including the NASA Distinguished Service Award (2000), the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal (2009), and the National Science Board's Vannevar Bush Award (2013).

"Understanding our planet's systems — and the interactions that shape them — is an enormously complex task. It will take the combined efforts of biologists, ecologists, physical scientists, computer scientists, engineers and social scientists. Much of the research excitement today is at the boundaries of disciplines."

– Rita R. Colwell, October 1998

Dr. Rita R. Colwell served as the 11th director of the National Science Foundation from August 1998 to February 2004. An internationally recognized expert on cholera and other infectious diseases, Colwell was the first woman to serve as director of NSF and was the first director in more than 25 years with training as a biologist. During her six-year tenure as director, she oversaw a 68% increase in NSF's budget, championed innovative science and engineering education programs, and increased funding devoted to advancing women in academic engineering and science careers.

Before NSF

Despite being cautioned by her high school teachers that science wasn't for women, Colwell embarked on a career in science out of, in her words, "sheer stubbornness." She earned a B.S. in bacteriology and an M.S. in genetics from Purdue University and a Ph.D. in oceanography from the University of Washington.

Colwell's distinguished academic career encompasses several tenured professorships, around 800 scientific publications as well as numerous books, and over a dozen leadership appointments to various government and academic advisory boards. After receiving her Ph.D. in 1961, Colwell served as a guest scientist at the National Research Council of Canada until 1963, when she joined the faculty at Georgetown University as a visiting assistant professor in the biology department. In 1964, Colwell was promoted to the rank of associate professor with tenure and, in 1972, left Georgetown to join the faculty at the University of Maryland as professor of microbiology.

In 1983, after more than 20 years of teaching and research, Colwell began advising and directing education policy and initiatives as vice president for academic affairs at the University of Maryland. In 1987, she broadened her influence over the direction of the university's academic affairs, serving as founding director of two major research centers at the University of Maryland: the Center of Marine Biology and the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute. In 1991, she was chosen to serve as president of the University of Maryland's Biotechnology Institute, a position she held for seven years until she was appointed NSF director in 1998.

Colwell also held leadership positions in a number of professional societies and governing boards. To name just a few: From 1973 to 1998, Colwell served terms as president of the American Society for Microbiology, president of the International Union of Microbiological Societies, president of the Washington Academy of Sciences, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and president of the International Congress of Systematic and Evolutionary Biology. From 1983 to 1990, she served on the National Science Board. In 1997, she was appointed to the Biodiversity Subcommittee of the President's Committee on Science and Technology.

Director of NSF

In August 1998, Colwell was sworn in as director of the National Science Foundation. As director, she brought her interests in interdisciplinary research, biocomplexity and pre-collegiate education to bear on the direction of the NSF.

Colwell saw the agency's budget increase by 68% during her tenure as director. She directed the increased funding toward a variety of new programs designed to, as she described in one interview, "keep America preeminent at the frontier of research and education." In an effort to "raise the productivity of U.S. science and engineering," she also championed the increase of grant award sizes, which rose from an annual average of $90,000 in 1998 to $142,000 in 2005.

As director, Colwell promoted innovative research collaborations across traditional disciplines, such as biocomplexity in the environment, nanoscale science and engineering, and bioinformatics and information technology. She also directed increased funding toward starting new education programs. One such initiative was the widely praised "GK-12" program, which placed promising science and engineering graduate students directly in K-12 classrooms so that they might spread enthusiasm for science while also learning about the challenges of science education.

In 2001, Colwell oversaw the creation of NSF's ADVANCE program, which was established to increase the representation and advancement of women in academic engineering and science careers. ADVANCE supported women pursuing science careers through a variety of funding opportunities, including Fellow Awards designed to assist women during career leaves of absence to fulfill family obligations, Institutional Transformation Awards aimed at developing institutional procedures for encouraging women faculty to hold leadership roles, and Leadership Awards designed to recognize the efforts already made by institutions and individuals to encourage women in engineering and science careers. Before finishing her tenure as director, Colwell oversaw the doubling of funding for ADVANCE.

After NSF

In 2004, at the close of her tenure as director, Colwell assumed the position of chairman of Canon U.S. Life Sciences, Inc. — a biomedical company specializing in developing life-science solutions with applications in diagnostic and medical instrumentation. In 2004, she also joined the faculty of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and served as distinguished university professor at the University of Maryland — a position she currently holds. In 2008, Colwell founded CosmosID, a bioinformatics company focused on microbial identification and pathogen diagnosis, which she currently chairs. In addition to being elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 2000, Colwell has won numerous awards including the 2006 National Medal of Science and the 2010 Stockholm Water Prize.

"One of the most significant ways in which government can stimulate discovery and innovation is to encourage international cooperation in research and education."

– Arden L. Bement, November 2008

Arden L. Bement, Jr. served as the 12th director of the National Science Foundation from November 2004 to May 2010. He served as acting director from February to November 2004 upon the departure of Director Rita Colwell. During his six-year tenure as director, Bement oversaw the establishment of the Office of Cyberinfrastructure, an increase in the NSF budget, and the broadening of NSF's international collaboration, to name a few highlights.

Before NSF

Bement trained as a metallurgical engineer, earning his B.S. at the Colorado School of Mines, his M.S. at the University of Idaho, and his Ph.D. at the University of Michigan.

Bement's diverse career spanned industry, government and academia. In 1954, Bement launched his career in industry as a senior research associate at General Electric. In 1965, Bement became manager of fuels, materials and metallurgy at Battelle Northwest Laboratories. In 1970, he left Batelle to take a position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as professor of nuclear materials. In 1976, Bement brought his multifaceted engineering experience to the federal government, directing science and technology policy and research and development as director of the Office of Materials Science for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA. From 1979 to 1980, he served as deputy undersecretary for research and engineering for the U.S. Department of Defense. In 1980, Bement joined TRW, Inc., where he served as vice president for technical resources until 1988 and vice president for science and technology until 1992.

In 1992, Bement returned to academia to assume the position of David A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Nuclear Engineering at Purdue University. He also served as head of the School of Nuclear Engineering and was jointly appointed to the Krannert School of Management and the departments of materials engineering and electrical and computer engineering.

In December 2001, Bement returned to government when President George W. Bush appointed him as director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. As director of NIST, Bement led organizational efforts to promote innovation and industrial competitiveness within the U.S. Bement administered an agency budget of around $773 million and an administrative and research staff of 3,000 employees.

Director of NSF

On November 24, 2004, Dr. Arden L. Bement was sworn in as director of the National Science Foundation. As director, Bement drew from his diverse experience working in industry, academia and government agencies to direct the only federal agency dedicated to funding basic research and education in all fields of science and engineering.

Bement's tenure as director witnessed a renewed commitment from the White House to expand federal funding of science and technology research and education. In 2006, President Bush announced the American Competitiveness Initiative, which was designed to increase American global competitiveness in science- and technology-intense sectors of the economy and which targeted NSF for budget increases over the next 10 years. Additionally, the Obama Administration's 2009 "American Recovery and Reinvestment Act" signaled increased federal spending on science and education as a key to federal stimulus. As a result, Bement oversaw a one-time spike in the NSF budget to over $9 billion in fiscal year 2009.