Geochemists solve mystery of Earth's vanishing crust

Earth's crust is the solid, outermost layer of our planet. Much of what happens below that layer remains a mystery, including the fate of sections of crust that vanish back into the Earth.

Now, a team of geochemists based at the Florida State University-headquartered National High Magnetic Field Laboratory has uncovered key clues about where rocky sections of oceanic crust have been hiding.

The National Science Foundation-funded research has provided fresh evidence that, while most of the Earth's crust is relatively new, a small percentage is made up of ancient chunks that had long ago sunk back into the mantle and later resurfaced. The researchers also found, based on the amount of that "recycled" crust, that the planet has been churning out crust consistently since its formation 4.5 billion years ago -- a picture that contradicts prevailing theories.

The research is published in the journal Science Advances.

"Like salmon returning to their spawning grounds, some oceanic crust returns to its breeding ground, the volcanic ridges where fresh crust is born," said co-author Munir Humayun, a MagLab geochemist. "We used a new technique to show that this process is essentially a closed loop, and that recycled crust is distributed unevenly along ridges."

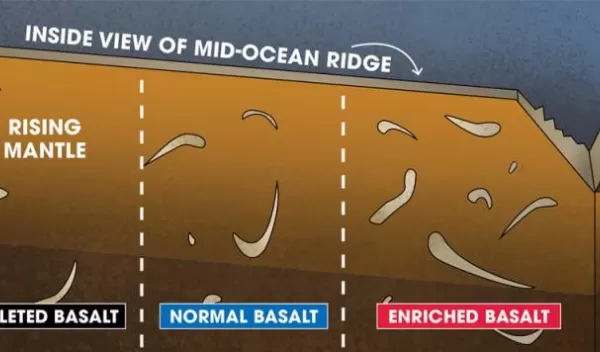

The Earth's oceanic crust is formed when mantle rock melts near fissures between tectonic plates along undersea volcanic ridges. As new crust is made, it pushes older crust away from the ridges and toward continents. Eventually, it reaches areas called subduction zones, where it is swallowed back into the Earth.

Scientists have long wondered what happens to subducted crust after it returns to the hot, high-pressure environment of the planet's mantle. It might sink deeper into the mantle and settle there, or rise back to the surface in plumes, or swirl through the mantle, like strands of chocolate through a yellow marble cake. Some of that "chocolate" might eventually rise up, re-melt at mid-ocean ridges, and form new rock for yet another millions-of-years-long tour of duty on the seafloor.

The new evidence supports this "marble cake" theory.