One giant leap for womankind: Women at the South Pole

On November 12, 1969, six women linked arms as they walked down the ramp of a large, ski-equipped Navy transport plane in Antarctica. Lois Jones, Terry Lee Tickhill Terrell, Kay Lindsay, and Eileen McSaveney — all researchers from Ohio State University — were joined by Pam Young, a scientist from New Zealand, and Jean Pearson, a reporter for the Detroit Free Press as they stepped onto the ice near the Earth’s southernmost point. With that final step, they became the first women to visit the South Pole.

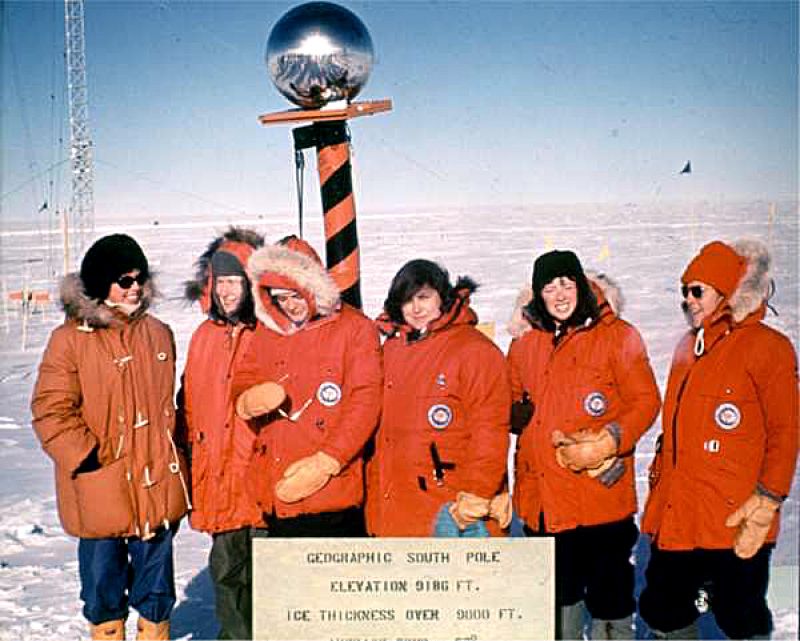

After lunching with a group of researchers and Navy men working at the Amundsen-Scott research station, the women posed for a photo in front of the iconic, mirrored marker for the geographic South Pole before boarding a transport plane back to McMurdo Station, located on the Antarctic coast. Though they’d just made history, they were anxious to turn their attention to what had brought them to Antarctica in the first place — research.

Research in the Dry Valleys

Mysterious lakes in Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys had led Lois Jones, the head of the all-women Ohio State research team, to Antarctica. She first learned of the deep, salty lakes that dot the frozen continent as a graduate student. Jones became fascinated with their existence and ability to remain liquid despite freezing temperatures. Upon the advice of her advisor, she decided to make them the subject of her Ph.D. dissertation. Jones knew that she needed to travel to Antarctica to further her research.

The geochemist faced a challenge, however. It was the 1960s and no American woman had ever travelled to the continent of Antarctica for research with the United States Antarctic Program (USAP). Since the USAP’s creation in 1959, only men had made that journey – Mary Alice McWhinnie was the first woman to participate in the USAP, in 1962, but carried out her research on an offshore research vessel.

Though anyone could technically apply for a research grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency which managed the program (and still does today), it was up to the Navy, which provided travel and logistical support to NSF’s Antarctic program, whether to permit women on the ice.

Jones persisted.

She began her dry valley research from Ohio by getting her hands on any rock samples from the region that she could find. A male graduate student in her program even traveled to Antarctica on an NSF grant to collect additional samples for her study. After he couldn’t access some of the areas that Jones needed for her research, she became convinced that she needed to do her own field work.

In 1969, Jones earned her doctorate. Around the same time, she began hearing rumors that more and more women were trying to get grants to conduct research in Antarctica, and that the Navy might lift its restrictions.

“Can you imagine a male scientist answering a question like that?”

Jones submitted a detailed NSF proposal that outlined a 10-week research program for a small team in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. In June 1969, Jones learned that her proposal had been accepted and that the Navy had agreed to take four women to Antarctica. Jones and her team were officially ready to go.

In the lead up to the trip, they spent hours studying maps and checking equipment lists. Their groundbreaking expedition was generating considerable media buzz, though, and they couldn’t escape the flood of reporters. In an interview years after her trip, Jones remembered the “silly questions” that reporters asked.

“‘Will you wear lipstick while you work? How will you have your hair done?’” she recounted. “Can you imagine a male scientist answering a question like that?”

Upon hearing of Jones’s trip, one veteran of the Antarctic program reportedly quipped disapprovingly, “The only place left [for men] now is the moon.”

Jones, Lindsay, Terrell, and McSaveney had planned to work from McMurdo. But when they arrived, they learned that they would do even more than become the first American women performing research on the continent. They would also be part of the first group of women from anywhere in the world to visit the South Pole, nearly 1,000 miles away.

Pam Young, a New Zealand researcher working in collaboration with the USAP, and Jean Pearson, a journalist from the Detroit Free Press joined Jones’s group at McMurdo Research Station. On Nov. 12, 1969, the women boarded a Navy plane bound for the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Jones remembered thinking that the women would be able to quietly duck off the plane to explore once it reached the South Pole. To her surprise, though, the Navy had assembled a group of photographers to document the historic occasion.

As they linked arms and walked down the cargo ramp, the women cleared the way for others to follow in their footsteps. Over the past 50 years, hundreds of women have travelled to Antarctica as researchers, technicians and support staff of the USAP. As Mary Odile Cahoon, one of the first American women to winter on the continent in 1974 reasoned, “If women are in science and science is in the Antarctic, then women belong there.”